By David A. Björnsson

Over the holidays, I was watching one of so many bad Santa movies out there, and a staggering statistic was thrown out by the not-so-jolly main character. Somewhere amongst a hail of bullets, the embattled Santa blurted out that Christmas was now a $3 trillion a year worldwide industry. Was this true, or was it just an attention-grabbing exaggeration?

Clearly, I was going to have to fact-check this gun-toting Santa.

Sure enough, in October of last year, the National Retail Federation predicted that holiday spending would fall just shy of a trillion dollars ($989 billion) in the U.S. alone, for 2024. That’s up more than $50 billion from 2023, having more than doubled since 2004 ($467 billion). Granted, European numbers can be a little harder to pull together, but with more than twice the population, even if they only spend an estimated fifth of the American consumer, it still ends up pushing another half a trillion dollars.

So while Santa may have been shooting from the hip in the aforementioned movie, when he threw the number out there, if you add in all of the other countries in the world that celebrate Christmas, maybe he wasn’t that far off after all.

Where will Santa go when the North Pole melts?

In this tongue-in-cheek parody, it was not so subtly pointed out that the white-bearded archetype and jolly persona of Old Saint Nick had become the enduring icon of yearend commerce throughout the world.

Unlike the days of old, our beloved childhood father figure, traversing the night sky after double-checking his naughty and nice list, has been designated to bring joy to the world almost exclusively in the form of bigger and bigger piles of material goods. Unwittingly, he now sustains our endless growth economies, at ever-increasing unsustainable levels.

But, much like the rest of us, he does this risking his own home – and future livelihood.

But bad Santa movies aside, what do any of these numbers have to do with the melting of the North Pole? Nothing. Or at least that’s what we’ve been led to believe by those pushing a stockholder-focused, endless growth economy. Nothing more to see here, but please buy more stuff on your way out.

And yet, if we care to look under the hood, we realize that it takes enormous amounts of energy and resources to make the stuff that ends up under the tree (then in our garages, storage units, and/or landfills). Energy and resources are depleting at an alarming rate. As a result, we are heating up the planet’s oceans and atmosphere through the burning of fossil fuels. Simultaneously, we are eliminating football fields of old-growth forests in the Amazon every minute.

That’s a terrible combination. Unless, of course, the goal is to eliminate the possibility of a livable planet, the paradise that we now enjoy.

But how do we know that our shopping habits and holiday travel are causing any disruption at all to the North Pole, let alone all the glaciers and ice sheets around the world? How do we know that an economic theory that goes against its own fundamental principles (confirming that the economy is based on limited resources) might just end up becoming the final straw when it comes to global stability, a working economy, and a viable future?

I know these are big questions, and here I reeled you in with Christmas shopping trivia. So let me back up for a moment and tell you a little bit about how I got concerned (really concerned) with where things are headed. It was the moment that my reservations about what we are doing to our environment became more than just an academic exercise for me. It became a rude awakening and deeply visceral insight. As it turns out, it’s happening to more and more people every year that passes.

How does climate change harm communities?

You see, just over 20 years ago I found myself standing chest-deep in my driveway, in floodwaters that had literally rushed in overnight.

On the first floor, my kitchen counters and dining room table were fully submerged, as was my fully finished basement below them. But, of course, it wasn’t just our home. Since the Coast Guard rescue chopper had nowhere to land, my neighbor, her children, and her mother had to be boated out of their second-story window.

Saying that it was surreal is a bigger understatement than many of us can imagine.

Our street, as well as the entire downtown area, were submerged. Having been declared a state of emergency by President Bush, the National Guard was brought in to secure the parameter. Meanwhile, everyone affected hauled their belongings and gutted out floors, walls, and insulation into large mounds of debris on their curbs since many things would be instantly trashed once submerged in floodwaters, including appliances and vehicles.

In hindsight, this was the onset of the climate crisis in our area. Since then, we’ve been flooded 5 times in a town that wasn’t previously prone to flooding. And this wasn’t New Orleans or any other place that had been in the headlines up until then. This was in the middle of New Jersey. We had never been on national television before. Granted, just about everyone on our street has since been elevated, but that doesn’t change the fact that the weather patterns are shifting.

In relaying the story, I’ve frequently been asked why we didn’t just move. In return, I ask whether they’d like to buy a house that’s been flooded multiple times and how much they would be willing to pay for it. It’s always a lightbulb moment.

These changes in global weather patterns, along with the increase in the intensity of natural disasters, are due to the annual rise in the heat in the oceans as well as the atmosphere. As a result, more and more people are beginning to encounter the direct impact in the U.S. and around the world.

A growing number of people now have a story similar to mine or worse, whether it’s having their homes ripped from their foundation by a hurricane, tornado, or flood. If not, they are shredded entirely or destroyed in yet another wildfire. These lived experiences are becoming more and more commonplace. And then there are the heatwaves and the droughts impacting large areas of the planet, killing both crops and people.

Why is melting ice so bad for the planet?

There are, of course, those who will tell us that the Earth goes through cycles and that we should not be concerned with a little melting ice, high water events, droughts, wildfires, hurricanes, tornadoes, or heat waves… even if these keep breaking records year after year.

These aren’t climate scientists telling us this. In fact, climate and Earth systems scientists are warning us of the exact opposite. Systems scientists, like Johan Rockström, point out that we’ve enjoyed the stability of +/- half a degree Celsius average variable since the last ice age. It’s global climate stability that has cradled humanity in what’s called the Holocene, which Rockström has dubbed “The Corridor of Life.”

It’s this corridor that we’re on track to leave.

With all the talk of the natural variation in temperature between past ice ages, we haven’t exceeded 2° C in the past 3 million years, and yet we’re currently on track for 2.7° C. That’s well past the 1.5° C we’ve been warned not to surpass.

But what’s a degree or two – Celsius or Fahrenheit? After all, the variation in daily temperature can fluctuate substantially, and we’re all still here. Well, except for the tens of thousands caught in rising heatwaves, of course.

The temperature of the Earth, calculated as an average throughout the year, is a different concept altogether. That’s more like our body temperature. Here, a couple of degrees rise means you have a fever, which is a warning sign for an adult and can become a matter of life and death for a child or an elderly grandparent. That’s what’s happening to our planet.

When Barack Obama took office, in the housing market free-fall of 2008, his advisors were telling him that these issues were 50-100 years out. By the end of his second term, in 2016, Obama was being advised that this was a much more immediate issue than previously thought.

Before he left office, he did a Rolling Stone interview in Alaska to stress the fact that the permafrost there was already melting. All the while Miami was elevating their streets due to sea level rise. He confessed, “Every time I get a scientific report, I’m made aware that we have less time than we thought.”

But, since I brought it up, let’s focus on the amount of ice melting for a moment.

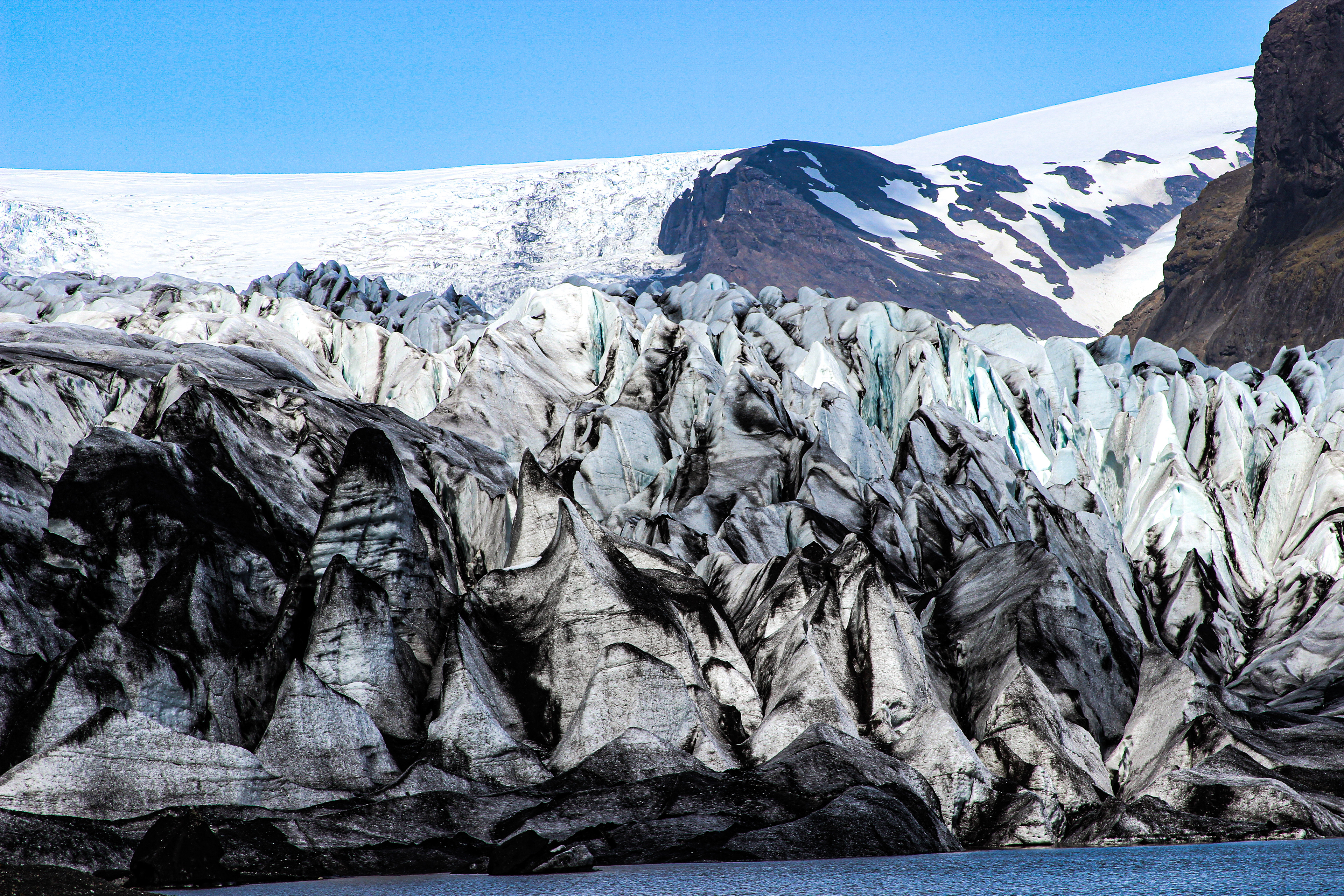

Given that I was born in Iceland, this issue hits close to home, literally. As Sarah Palin would no doubt put it – “I can practically see Santa’s workshop from my house.” But in all seriousness, growing up, I could see one of Iceland’s most famous glaciers, Snæfellsjökull (Snowfall Glacier) out my bedroom window, some 70 miles (112 km) away.

Now, this glacier and so many others might just become the proverbial canary in the coal mine. In fact, when the first glacier, Okjökull (Ok Glacier), lost all of its snow and ice, it was unceremoniously downgraded to just Ok, in 2014. This is, of course, far from Ok.

In 2008, 11% of Iceland’s land was covered in glaciers. As of 2019, it’s dropped to 10% and waning. Keep in mind that while this indicates at least a 9% melt rate in less than 2 decades, and it doesn’t account for accelerated melting as temperatures rise.

Then there’s the unfortunate casualty of an American tourist in Iceland this past summer.

A melting ice cave collapsed on top of him. Luckily, the man’s pregnant girlfriend and the rest of the tour group survived, but this was a foreseeable and avoidable tragedy.

Foreign booking agents are pushing further and further past common sense and national guidelines, as well as the warnings of local tour guides. When you dig a little deeper into the story it becomes obvious that it’s a microcosm of our slow response to a climate we are so rapidly changing and our blind dedication to profit over people and planet.

What happens if ice sheets melt?

Stories like these don’t get the airtime they deserve.

However, if you look for it, there is an abundance of good information and solutions. Among them is Vice President Al Gore’s impassioned warning at the United Nations Climate Change Conference this past November about the rate of glacial melting. This is but one example of the way that the alarm should be sounded: with a sense of urgency and frustration.

He points out that losing 30 million tons of ice per hour from Greenland’s massive ice sheet is more than just concerning. That’s over 270 billion tons (or 270 gigatons) of freshwater ice pouring into the ocean every year (by the way, 1 gigaton equals 2.2 trillion pounds). He referred to it as the potential collapse of a pillar of our ecosystem, with a massive tipping point attached. And, again, this is not 100 years from now, or even 50. No, we’re on track for 2050, maybe sooner. For those who have just been blessed with a baby or a grandchild, that’s around the time that child would be graduating college. If you’re in your 40s now, that’s before you’d retire at 65. That’s possibly the time that Santa has to pack his bags, but like so many others, he has nowhere to go.

Hopefully, there will be enough public outcry and activism before we get to that point. We just have to remember that this is a moving train and by the time we actually hit the breaks, we will still be moving forward for quite some time before we come to a full net zero stop. So the time is now to start focusing on saving the only home we know from ourselves.

Granted, there are probably a fair number of people who don’t care about the fact that a place like Antarctica is considered a natural wonder of the world. But let me put this into perspective for a moment. Where does most of our freshwater come from? Almost 70% comes from icecaps and glaciers. But that’s far from the only concern. The way that ice and snow reflect the sun’s rays plays a critical part in keeping our planet cooler than it otherwise would be. When the North and South Poles disappear, along with all the glaciers in between, we lose that desperately needed cooling advantage.

What are nature’s early warning systems?

Then there’s the issue of the rise in sea level if we end up melting all of the ice on the surface of the planet.

The current refrain from so many environmental advocates these days is that people who have the lowest carbon footprint will be the ones suffering the greatest amount of consequences. While it may be true that the initial effects are first being felt on low-lying islands, supposedly “out there somewhere,” it won’t be long before they will be undeniable in places we don’t often think of as vulnerable.

To get the necessary perspective on why melting our glaciers is such a looming threat, let’s take a trip to Iceland once more.

Along with 268 other glaciers, it’s home to the largest glacier in Europe, Vatnajökull (Water Glacier). It has a maximum thickness of 3,280 feet (1,000 meters). That’s taller than the tallest building in the world, the Burj Khalifa (2,717 feet/828 meters) in Dubai. Meanwhile, the average thickness (1,450 feet/442 meters) is still greater than the height of the Empire State Building (1,250 feet/380 meters). Yet, this still pales in comparison to Greenland’s ice sheet, right next door to us, which clocks in at a thickness of over 1.9 miles (3 kilometers).

Then there’s the Viedma Glacier, part of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, the second largest ice field in the world, located on the Chile/Argentinian border. It touts a thickness of nearly a mile (1,400 meters). Then again, we haven’t even covered Alaska, the Himalayas, the Swiss Alps, or the Rocky Mountains, stretching from the U.S. to Canada. In fact, there are ice sheets and glaciers all over the world, even in Africa.

This brings us to the mammoth of them all, the Antarctic Ice Sheet, which is 3 miles (4.9 kilometers) at its thickest point, with an average of 1.2 miles (2 kilometers). It would raise global sea levels by 190 feet (58 meters), out of the estimated 230 feet (70 meters) if all the glaciers and ice sheets melt in coming heatwaves. This would leave the Statue of Liberty chest-deep in floodwaters, not long after our planet’s glaciers first start swishing in and out of homes, bars, restaurants, boutiques, and other businesses in places close to home, depending where in the world you live; places like, oh, I don’t know, Buenos Aires, Miami, Reykjavík, London, Copenhagen, Barcelona, Cairo, Tokyo, Sydney, San Francisco, New York City, and Washington DC.

Are there solutions to climate change?

We’ve covered a lot of troubling ground here, for sure.

To those of us concerned about our impact on the environment, upon which we all depend, these are alarming numbers. The good news is that people who have been warning about the impact of a no-holds-barred approach to running the planet, like Noam Chomsky, still hold out hope. He recently stated, in his Masterclass ad: “For every serious problem we face there are feasible answers.”

Thankfully, there are solutions being implemented around the world.

At their current rate of success, however, these solutions are no match for the juggernaut that is our current rate of consumption of energy and “goods” – which could just as well be defined as “bads” at this point. Unless, of course, we start to discern between sustainable goods and unsustainable bads, whether talking about the production of energy, products, or travel.

Perhaps we need a far more drastic approach to solving the climate crisis.

After all, as U.S. Treasury Secretary, Janet Yellen, urged at the G20 in Brazil this past summer, we need $3 trillion in new capital every year to transition to a low-carbon economy. Wait, where have I heard that number before? Don’t tell me. Shhh, it’s coming to me. Oh, yes, that’s right! It’s the same amount we spend on carbonating our atmosphere every Christmas! What a coincidence!

Now here’s a radical idea: What about adapting the birthday challenge that Charity Water launched years ago, where you give up your gifts and instead donate the equivalent to charity, we could start with forgoing Christmas gifts and travel to send a message to the retail industry that we only want sustainable products? Instead of planned obsolescence, we want alternative fuel for our planes and cruise ships, as they bring tourists up close to the spectacle of massive walls of snow and ice as they break off in colossal chunks. This way we could fund the de-carbonizing of our atmosphere every year until we see a reversal of the damage that we are doing to our own home.

Either way, the path to a sustainable future, where we don’t end up sinking Santa’s workshop, along with our own homes, begins with self-awareness and being better informed.

If we are to find a way to live in harmony with nature, instead of watching it come undone, the goal should be to enhance our understanding of the consequences of our collective actions and find ways to mitigate them. That’s when we can become effective advocates in our own communities and circles of influence.

As more people gain a visceral understanding, whether through being impacted by a natural disaster or seeing the natural wonders of the world up close, perhaps we can find a way to reconnect to nature in a way that will make us worthy ancestors to the generations already here and those to come.

Leave a comment